What is internationalisation all about? What are the implied opportunities and challenges, and what does it all mean for university people?

Intro by Klaus Mohn, rector and professor, at University of Stavanger panel talk.

I am very happy for the opportunity to participate in this panel talk on internalisation to engage us all on a topic which is crucial to the future of Norwegian universities. What is internationalisation all about? What are the implied opportunities and challenges, and what does it all mean for university people? But before we dive into the specifics of today’s topic, allow me to take a few steps back, and share some background and context.

When I took the helm as rector nearly three years ago, a proposal for our university was to make efforts to improve at everything we do. A requirement was a more systematic approach to quality management in all our core activities. The way we do research, the way we do education and supervision, the way we do innovation and community outreach, and the way we run our organisation.

Together we have combined efforts across the organisation, in our new strategy, in our plans for research, education, innovation and outreach, in the management and operation of our organisation and infrastructure, and not least, in strategies and plans at the faculty level. And it works! After only two our concert of efforts is already starting to produce promising progress. This is something we all should be proud of.

All the help we can get

Building a better university is true teamwork. Each and everyone of us should therefore consider how we contribute to the aspirations and ambitions of our university. To the greater good. Surely, the university gains from excellent individuals. But our people also gains from the university’s reputation. At the end of the day, we are all in the same boat.

Our ambitions can not possibly be met without widespread interaction with the world around us, on a regional level, on a national level, and not least on an international level. We need help from wherever we can get it. This is where our international staff comes in. And make no mistake: We are flattered by your interest in working for our university. Take my word that your contribution is highly appreciated. In return, our hope is that you maintain correspondingly favourable feelings for your employer.

Means to an end

Broadly speaking, internationalisation can be seen as the development of our interaction with the world outside Norway. Although it involves a range of important arenas and activities, internationalisation is not an aim in itself. Rather, it is a mean to an end. And that end is to build a better university.

Internationalisation contributes very favourably to the development of Norwegian academia in general, and to the University of Stavanger in particular. Our own records of publication and citation carry clear evidence of the benefits of interaction with the wider world. The diversity of our work place has also benefitted from internationalisation, and our teaching and supervision are increasingly inspired by methods and practices from the international academic community.

At the same time, aspirations and ambitions for our university are formed by a broad set of stakeholders, including yourself. But we also have to lend ears to our Norwegian employees, internal and external groups of interest at the regional and national level, including our board – and not least our owner, the Norwegian government. This coalition of interest raise expectations for us on a range of areas.

In consequence, internationalisation have to be balanced against our commitment to also meet national interests, expectations, and requirements. We should combine our history and heritage, our capacity and competence, our Norwegian culture and language, take inspiration through internationalisation and input from all available sources, to develop a first-class Norwegian university.

Rapid recruitment

Over the last five years the share of non-Norwegians in our staff has increased by nearly ten percentage points (from 18 to 27 per cent), and the total number of international employees has nearly doubled, from just below 300 in 2017 to nearly 600 this year. It would seem that our ability to recruit internationally accelerates due to self-reinforcing feedback-mechanisms.

This development has also been supported by our HR strategy and action plan, calling explicitly for a more professional approach to recruitment in general, and to international recruitment in particular. International announcement of vacant positions is now more of a rule, whereas announcement in Norway only is the exception. It used to be the other way around.

Obviously, there is also variation across our organisation. Our Faculty of science and technology has a long tradition of international recruitment, but the Faculty of arts and education, The Faculty of social science and the UiS Business school are now all picking up speed. This also implies that our response has to be diversified according to the needs of each faculty and department.

New people add quality

Also bear in mind that certain research projects and teaching obligations at the undergraduate level still require skills in Scandinavian language, and present potential boundaries for international recruitment. Whatsoever, new people who add quality to our core activitites – and to our culture – is good news. That goes for all employees, irrespective of origin. Other elements of internationalisation have also contributed positively to our performance, like international partnerships and alliances, research cooperation, student exchange, and international teaching and supervision practices.

Although the process of internationalisation seems to have picked up speed over the last few years, it is not an entirely new phenomenon. Our international office was established more than ten years ago (2011), and in 2012 we joined the European Consortium of Innovative Universities ( ). This alliance has subsequently gained traction and qualified for grants under the European University Initiative. In 2019 we established the Euraxess Mobility Center in our HR department, to assist international mobility, recruitment, and onboarding processes across the organisation.

Even if internationalisation is not explicitly stated as a strategic aim in its own right, I take it that you will recognize that its importance is reflected on our general agenda. Cooperation and collaboration, international recruitment, mobility among employees and students remain crucial elements in our efforts to lift the quality of core activities at the University of Stavanger.

Norwegian is our main working language

An obvious source of challenges to internationalisation stems from language barriers. We take for granted that our students and staff need a proficient command of English. However, we can not take for granted that our international employees will be fluent in Norwegian once they start at their job here in Norway. As rapid recruitment might also have stretched our absorption capacity, language barriers raise challenges that call for attention, debate and response.

In line with policies and requirements from our Ministry of education and research, a language policy guideline was established for our university in 2020. Norwegian is the main working language at the University of Stavanger, and that is not going to change. However, working and teaching languages in everyday life are Norwegian and English. Both academic and administrative staff use English whenever necessary or suitable.

Bilingual skills bring out the best

Our language policy calls for the university to encourage employees and students to develop goods skills in both Norwegian and English. We can not do without Norwegian. In this area, our flexibility is limited by our responsibility to comply with university regulations and policies. As a Norwegian university, we have a clear responsibility to maintain and develop the Norwegian academic language. Our linguistic infra structure for communication on the national scene is already under pressure. Command of Norwegian is important for our students and employees to be able to engage with Norwegian society, through dissemination of research, collaboration with private and public enterprise, expert advise, and engagement in traditional and new media.

Policy signals are clear. The latest budget award letter from the Ministry of education and research explicitly asks universities to make demands on our non-Norwegian staff to acquire skills in Norwegian. The government expects the universities to monitor the language situation closely in both research and teaching, and to take required measures if necessary. In this sense, we remain a Norwegian university, and have to balance various interests and concerns in our further pursuit of progress. A waiver of the requirement for our staff to learn Norwegian is therefore not on our menu of choice.

All this being said, I am the first to admit that the sharp increase in international staff over the last years has raised challenges, not only in terms of growing pains for the organisation, but also at the individual level. Whereas we all agree that international recruitment add valuable quality and competence, we have probably been somewhat sluggish in realising the challenges. This will have to be considered more carefully going forward, both at the faculty level and at the institutional level.

Evaluation and adjustment

A good learning and working environment is a prerequisite for progress, and a key strategic priority for the University of Stavanger. If our employees do not thrive, our university can also not thrive. This makes the follow-up of our international staff an increasingly important element of human resource management.

Our approach needs to reflect the opportunities of further internationalisation, but it shall also have to respond better to the implied challenges. International recruitment should still be encouraged, but we also need to take steps to improve our organisation and management to handle the increase in international staff. Requirements for skills in Norwegian can not be abandoned, but we might consider measures to modify the individual burden on aspiring academics. Each department should also evaluate the need for adaptation of information and communication according to local needs, and consider if some information should be offered in English.

Finally, our approach will have to balance a range of concerns. We should make sure that further internationalisation does not come at the expense of our responsibility for the Norwegian language, and also not for our engagement with our region and Norwegian society. Collaboration and cooperation with civil society in Norway is expected also from our non-Norwegian staff. I feel confident that all these issues will be evaluated in the next revision of our HR strategy.

Embrace diversity!

The University of Stavanger depends critically on a variety of stakeholders. A challenge to us all is therefore to strike the right balance between a wide range of interests and concerns. There is no escape from regional and national interests. At the same time, with our ambitions for the university, there is also no escape from internationalisation.

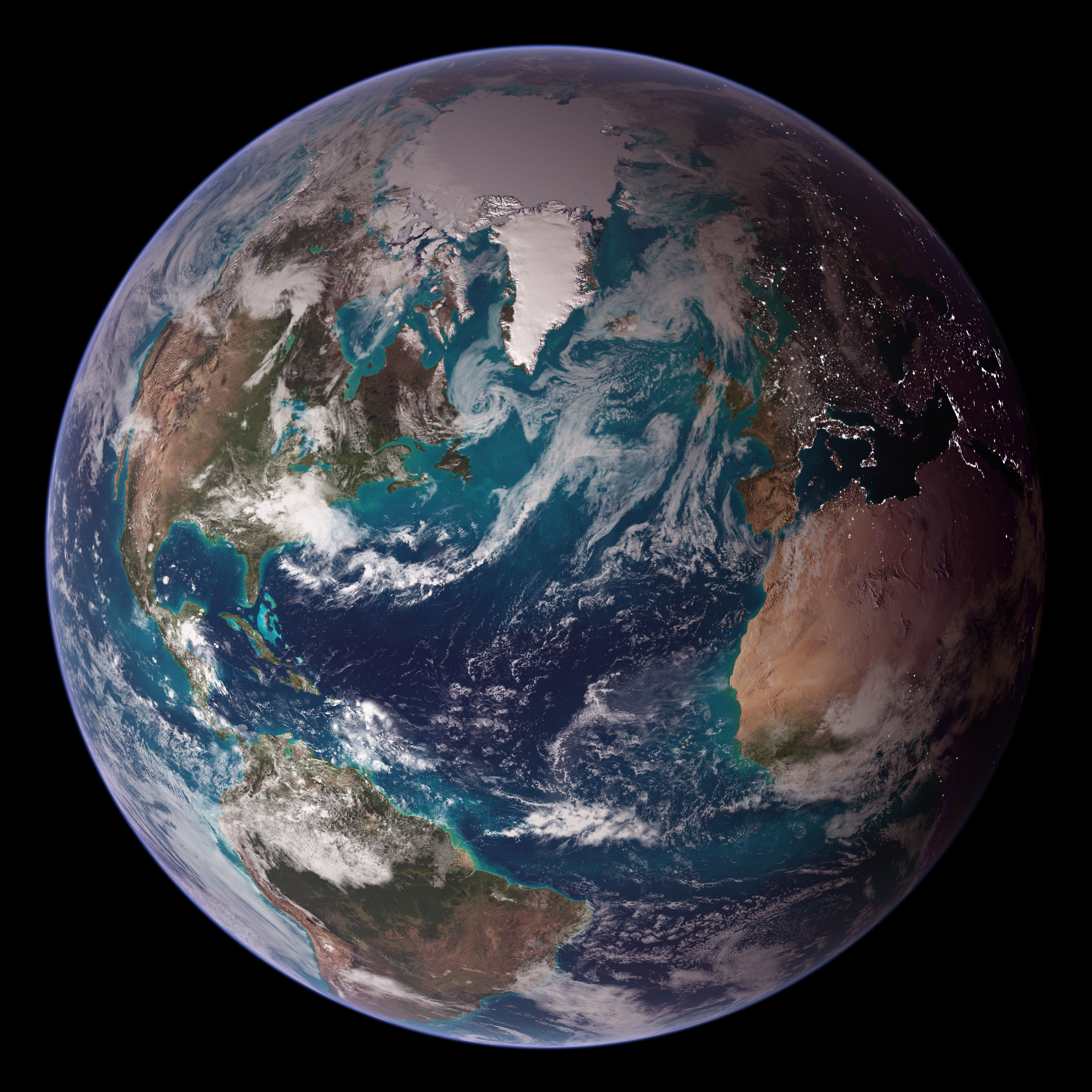

Although internationalization is not an aim in itself, our strategy and plans imply requirements for us all to engage with international communities on a broad scale. Frontiers of research, education, and innovation go far beyond nations. We aspire for improved quality in all we do. This can only be achieved if we relate actively to the wider world. The majority of societal challenges we are facing are also transnational, and even global. I follows that our response can not possibly be bounded by national borders.

I am convinced that diversity opens for more ideas, more perspectives, and improved performance. And a better work place - with more fun!

Thank you for choosing to work with us. Thank you for helping us build a better university.

Thank you for listening – and for engaging today.